The group will sample the material belongings of past people to document the practices of colonial and precolonial inhabitants of Fort Vancouver National Historic site. This year’s focus will be on the waterfront of the Columbia River along a strip of ground that holds archaeological resources associated with pre-contact American Indians, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), and the U.S. Army.

The waterfront is on the southern margins of the location of the Fort Vancouver Village, a multicultural settlement where engagés (employees) of the HBC and their families lived. American Indian, Native Hawaiian, European and other people from around the world lived in the Village. The waterfront provided access for trade goods and people arriving and departing from Fort Vancouver and its village. Most transport to the Fort occurred on lighters and smaller vessels but some larger ships also anchored there. In addition to a shipyard and boatshed, the HBC constructed a wharf to facilitate ship anchorage, and the loading and off-loading of supplies, equipment, and visitors. The wharf was probably constructed in 1827, as this was the year the HBC’s old docking area at Ryan Point (now the old World War II shipyards) was flooded.

Near the wharf and slightly to its east, a pond opened into the river (where the Vancouver Land Bridge is now), allowing passage of smaller vessels to anchor near several buildings. It is likely that sailors on shore may have built temporary dwellings and there may have been other employee’s residences. A salmon operation at the waterfront salted thousands of barrels of salmon a year, much of it for trade to the Hawaiian Islands. A salmon store, or fish house measuring 100 x 40 ft. was constructed near the wharf and a nearby “salt house” was used to store the salt used in preserving salmon, beef, and pork. A distillery is known to have been present by 1846. Tanning pits, likely for cowhide, a saw pit, pig and ox sheds, were situated further north.

One of the sites that the field school will explore this summer is a hospital that was tied to one of the first recorded pandemics that swept the lower Columbia River between 1830 and 1833. Robert Boyd has suggested that malaria swept through the region, described as “intermittant fever” and “fever and ague.” Malaria killed over 90% of the tribal peoples living along the lower Columbia River. In Boyd’s words, this was nothing short of apocalyptic.

The site of the hospital was first found during excavations in 1974, 1975, and 1977 by David and Jennifer Chance and Caroline Carley. They were exploring the area of the interchange between State Route 14 and Interstate 5 in the southwestern corner of the national park in front of a massive highway improvement project. Their work found Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader houses associated with the Fort Vancouver Village, artifacts from the U.S. Army Quartermaster’s Depot, and the pond filled with trash from both the HBC and early U.S. Army period. They also found the northern side of a palisaded hospital that was located near the pond.

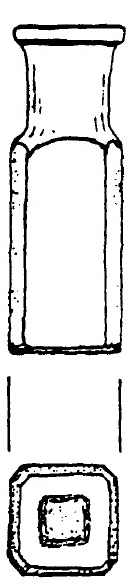

Three sides of a palisaded area, formed by posthole and trench features, were discovered. Based on historical evidence, the Stockade was interpreted as surrounding a hospital building. The archaeologists recorded a number of firepits, and five large, stratified pit features within the Stockade, and a cluster of burned pit features outside the Stockade. Possible uses proposed for the pits include smudge pits (for the creation of smoke for hide processing), smudging as a medical therapy (see below), refuse disposal, or storage. Artifacts found within the Stockade include medicine bottle and cupping therapy glass fragments, animal bone, bateau bolts and copper nails, clay pipe fragments, beads, buttons, and other objects. Carley suggested that the HBC built the hospital in the Riverside Complex, in addition to an infirmary inside the fort Stockade, because of the high number of people affected by the epidemics. The Hospital Stockade was used to quarantine people, and may have also excluded people when the hospital was at capacity. The firepit features may be due to the 19th century belief that contaminated air caused malaria, with smoke serving as a purifier. The large burned pits may be the result of cooking for so many patients (given the large amounts of burned animal bone), or the disposal of bedding and clothing (associated with many beads and buttons found in the pits).

This summer’s project will attempt to relocate the southern portion of the hospital as well as other evidence of the Riverside complex. Rediscovery of these sites will help in future rehabilitation of the Fort Vancouver waterfront and in the preservation and interpretation of these unique archaeological resources.