You heard a clank after you swiped your trowel, the most common tool used by archaeologists. It did not sound really crisp and clear, so you know that it isn’t part of a stone tool. This means that it is either bone, pottery, or another material. When you further dig around the area, you notice that there is a point sticking out of the ground, which makes you excited to know what you have discovered. Continuing to dig, the point turns out to be only a fraction of the entire piece. Taking a brush, another common tool that archaeologists use, you carefully clean the object you have just uncovered because you don’t want to damage the object with your trowel. After a closer look, you are able to see that it is a fishhook made from the tusk of a walrus, also known as ivory. You stick a metal flag in the ground next to your discovery to indicate where it was collected from.

It does not shock you that there is a fishhook present here in the northwest of Alaska at Cape Espenberg. It is quite common for the Thule (too-lee), one of the Alaska Native populations that lived in the area about 1,000 years ago, to make their tools for subsistence from things that come from animals like a caribou antler, a seal bone, and ivory. The Iñupiat (in-new-pee-at) present at the site today, who are descendants of the past Thule, like Fred Goodhope and his family tell you that their ancestors probably used the fishhook to fish for halibut in the springtime. You can’t help but think about how that belonging, now called an artifact, came from nothing to how it is found now, also known as a life history.

You can imagine a man in his winter lodgings that are made completely out of driftwood. There is a pot with the remaining coals of a fire next to him with his bedding of furs on his other side. Using the warmth and light from the fire, he is whittling away at the tusk of a walrus from a previous kill that the group hunted several weeks ago. The process is slow because the man does not want to break his precious work. This tool is going to be important for their group to fish in the coming season. The man can’t just buy a fishhook like you can today, so he needs to make one from material that can be found either through hunting or scavenging.

When the fishhook is finally complete, the man who constructed the fishhook and a few other men in the group would venture out into the water in the cape to fish in their umiak (oo-me-ack), a canoe made of wood and seal hide. Halibut are present in the area during this time of year and are delicious, so their goal is to capture several during this fishing session. Tying the fishhook to a stick with some twine, the man drops the fishhook in the water and waits for a nibble from their prey. When the fish bites, the men have to be very cautious because halibut can get really large. The other men on the canoe keep the paddles at the ready and their body weight off to one side to make sure the boat does not tilt too far or move too much while the man with the fishhook is reeling in the halibut. It would not be good for them to spend all that time and energy trying to catch this fish only to lose it.

The man knows that the environment has changed too much where the group is living currently. The new ridge is formed enough that their current lodging is not close enough to the coast for them. They know the group must move where they live. The man packs up his essentials because it would take too much effort to bring their entire living with them. The group packs up their stone tools, the umiak, bows and arrows, furs and skins, and leftover foods. This meant that the man left behind his ivory fishhook. He will have to make another for the next time the group needs to fish for their meals. The fishhook lies there in the lodging for centuries until the day that you find it with your trowel.

Life histories of artifacts are very important for archaeologists to think about. Archaeologists try to understand the importance of a belonging through its construction, its use, and its reason for its current condition where it is found, also known as discard. Archaeologists find what is left behind either because it is broken, abandoned, or lost. When it is broken or abandoned, like the ivory fishhook, the past people can view such belongings as trash. Archaeologists find the trash that people of the past have left behind or the belongings that have been lost to an individual.

Lab work and the analysis of artifacts is important to understand all parts of the life history of a belonging. These are important parts of understanding behavior of a culture. Archaeologists can understand behaviors such as transportation, subsistence practices, and how something is made from the culture they are studying through these life histories.

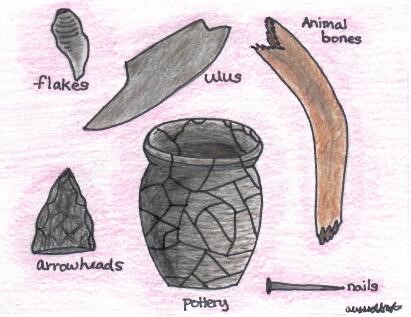

***Definition of ulu (oo-loo): translated to “woman’s knife” is a multipurpose knife that is used by Inuit, Iñupiat, Yupik, and Aleut women***

Like stories like this one? Check out some of these published stories that have an archaeological foundation and their brief descriptions from Goodreads:

Clan of the Cave Bear by Jean Auel (Book 1 from the Earth’s Children Series)

“This novel of awesome beauty and power is a moving saga about people, relationships, and the boundaries of love. Through Jean M. Auel’s magnificent storytelling we are taken back to the dawn of modern humans, and with a girl named Ayla we are swept up in the harsh and beautiful Ice Age world they shared with the ones who called themselves the Clan of the Cave Bear.”

What This Awl Means: Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village by Janet D. Spector

“This pioneering work focuses on excavations and discoveries at Little Rapids, a 19th-century Eastern Dakota planting village near present-day Minneapolis.”

Archaeology from Space: How the Future Shapes Our Past by Sarah Parçak

“National Geographic Explorer and TED Prize-winner Dr. Sarah Parcak welcomes you to the exciting new world of space archaeology, a growing field that is sparking extraordinary discoveries from ancient civilizations across the globe.

In Archaeology from Space, Sarah Parcak shows the evolution, major discoveries, and future potential of the young field of satellite archaeology. From surprise advancements after the declassification of spy photography, to a new map of the mythical Egyptian city of Tanis, she shares her field’s biggest discoveries, revealing why space archaeology is not only exciting, but urgently essential to the preservation of the world’s ancient treasures.

Parcak has worked in twelve countries and four continents, using multispectral and high-resolution satellite imagery to identify thousands of previously unknown settlements, roads, fortresses, palaces, tombs, and even potential pyramids. From there, her stories take us back in time and across borders, into the day-to-day lives of ancient humans whose traits and genes we share. And she shows us that if we heed the lessons of the past, we can shape a vibrant future.”

The Bog People: Iron-Age Man Preserved by Peter Vilhelm Glob, Elizabeth Wayland Barber, and Paul Barber

“One spring morning two men cutting peat in a Danish bog uncovered a well-preserved body of a man with a noose around his neck. Thinking they had stumbled upon a murder victim, they reported their discovery to the police, who were baffled until they consulted the famous archaeologist P.V. Glob. Glob identified the body as that of a two-thousand-year-old man, ritually murdered and thrown in the bog as a sacrifice to the goddess of fertility.

Written in the guise of a scientific detective story, this classic of archaeological history–a best-seller when it was published in England but out of print for many years–is a thoroughly engrossing and still reliable account of the religion, culture, and daily life of the European Iron Age.”

Another Arctic based story-

Sinews of Survival: The Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing by Betty Koyayashi Issenman

“Traditional Inuit attire has been used for protection, a sense of identity, and as culture-bearer for thousands of years. By preserving their clothing traditions, the Inuit celebrate their accomplishments, show pride in being a part of a unique culture, and affirm their lasting connection to the natural and spiritual worlds of their ancestors. Sinews of Survival draws together information about circumpolar clothing technologies, styles, and materials from 4000 years ago to the present. In this unique and beautifully illustrated book, Betty Kobayashi Issenman explores the living legacy of Inuit garment use and manufacture.

Sinews of Survival summarizes prehistoric finds related to clothing, describes the materials used, their characteristics, and the different items of clothing which are common throughout the circumpolar world. The tools are described at length as well as ingenious ways in which the Inuit prepared the material they harvested from animals, birds, and sea mammals. The text is accompanied by patterns and illustrations of seams and stitches which serve to highlight differences in style from one region to another and help identify historical clothing of different Inuit groups.

The author weaves together Inuit voices, drawings, and writings, giving a glimpse of a rich and layered culture which has survived some of the harshest living conditions in the world while abiding in ecological and spiritual harmony with its environment. While the focus is on the Canadian heritage, ample references to and images of Inuit clothing from Northeastern Siberia, Alaska and Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) help readers appreciate commonalities and differences. Written in accessible language with numerous photographs, Sinews of Survival is an important resource for Arctic scholars, anthropologists, and archaeologists, and for the general public it opens a door to Inuit culture.”

For children-

Archaeology: Cool Women Who Dig by Anita Yasuda

“How do we learn more about the people of the past? Through archaeology! Archaeologists are great detectives. They look for clues from the past, called artifacts, that have been buried for hundreds, even thousands of years. They investigate sites at the bottom of the sea, on land, and on mountain peaks. Archaeologists look closely at objects and where they were found on a site to discover who, what, when, where, why, and how people lived, from thousands of years ago to the recent past.

In Archaeology: Cool Women Who Dig, children ages 9 through 12 learn about this amazing field and meet three dynamic women who are working in archaeology around the world. Chelsea Rose is a historical archaeologist with Southern Oregon University, Alexandra Jones runs Archaeology in the Community in Washington, DC, and Justine Benanty is a maritime archaeologist from New York City.

Children will also be introduced to several pioneering female archaeologists, including Jane Dieulafoy, Gertrude Bell, and Harriet Boyd Hawes. These are people who strived to be successful in a field that wasn’t always welcoming to women. Nomad Press books in the Girls in Science series supply a bridge between girls’ interests and their potential futures by investigating science careers and introducing women who have succeeded in science. Compelling stories of real-life archaeologists provide readers with role models that they can look toward as examples of success.

Archaeology: Cool Women Who Dig uses engaging content, links to primary sources, and essential questions to whet kids’ appetites for further exploration and study of archaeology. This book explores the history of archaeology, the women who helped pioneer field research, and the multitude of varied careers in this exciting and important field. Both boys and girls are encouraged to find their passion in the gritty field of archaeology.”