Sagittaria latifolia is a perennial herb with an erect growth habit. The leaves are sheathing, and glabrous, and it is cosmopolitan in distribution, present throughout North America, northern Europe, and Asia. Wapato is a tuberous plant that can grow prolifically in immense, homogenous, wetland fields hundreds of acres in extent. The roots were an important food and trade commodity for the Native peoples who lived within the Northwest Coast cultural area. The tubers of this plant were called ‘wapato’ in Chinook wawa, (variations include wapato, pota, and waptoo) and the bread cake made from this plant was called chaplil.

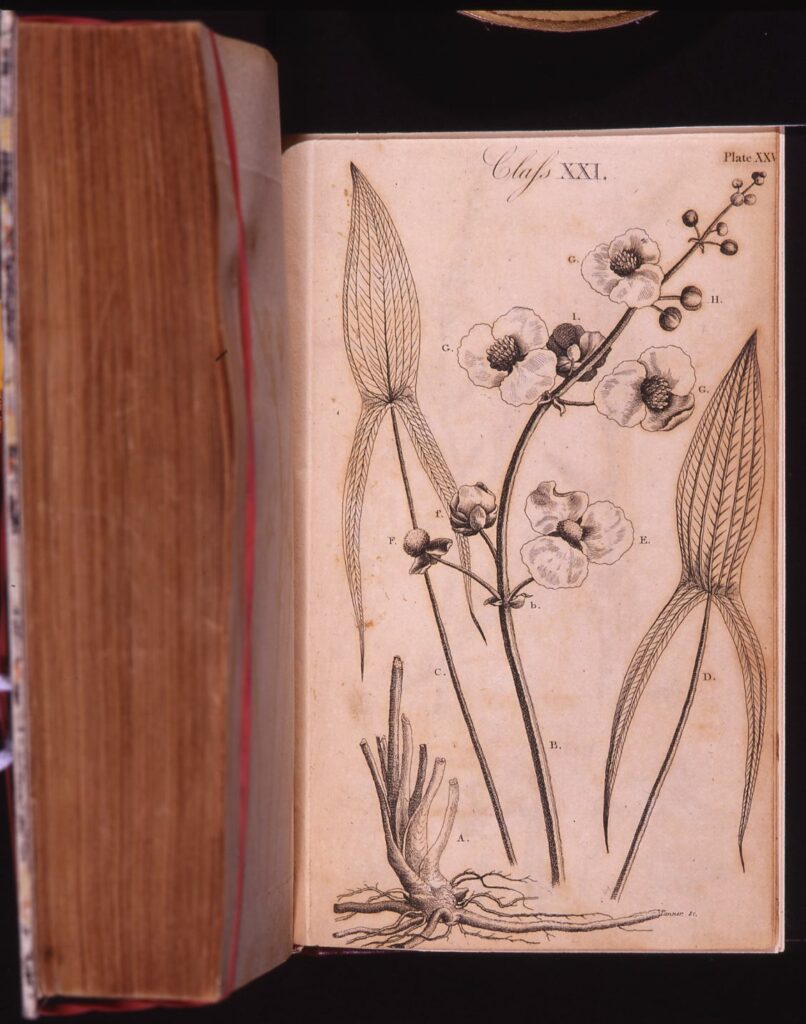

Though all the leaf forms are three-lobed and sagittate, there is some variation in form and size. The plants can grow to 150 centimeters tall, but are typically a meter or less. The flowers are white, in whorls of three petals, on a simple leafless raceme.

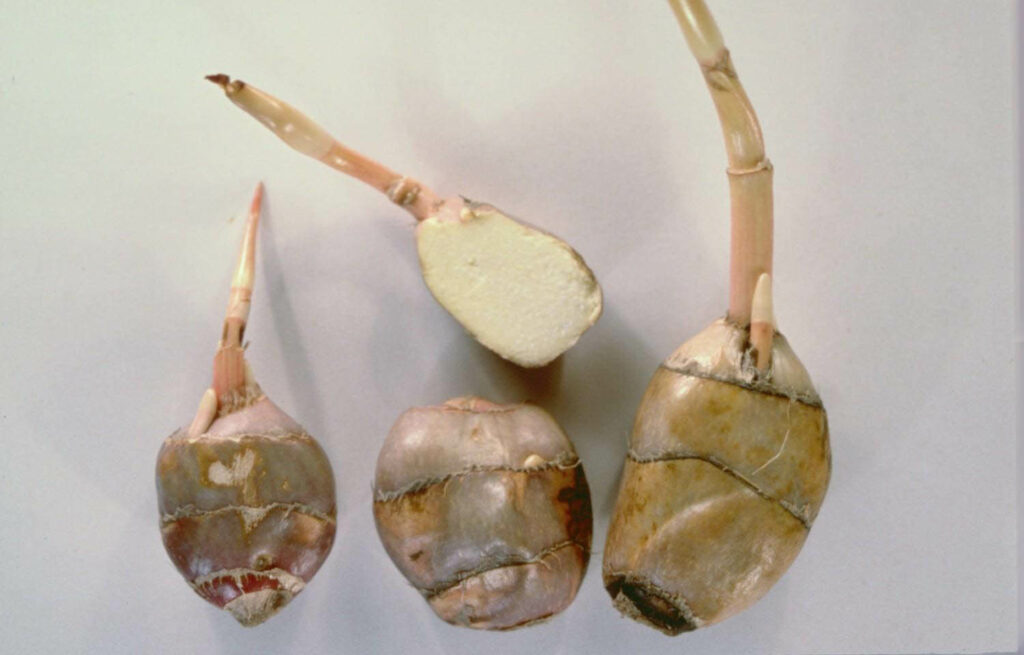

In Sagittaria spp., tubers are formed on the ends of long white rhizomes, which are horizontally creeping stems. By September on the lower Columbia, the distal ends of these rhizomes cease to produce new plants, rather they begin to thicken and develop into the starchy overwintering organ known as wapato. The below-ground biomass of the tubers is about a pound of wapato per square meter.

The tuber was often called ‘Indian Potato’ for its resemblance in taste and texture to a white potato, though it is smaller. Like potatoes, the small ones are as edible as the large ones

In the replicative experiments I conducted, I have found that wapato is cost effective to harvest. I have also found that it nutritious, highly palatable, stores well fresh or dry. It can be eaten raw, and cooks in hot ashes in ten minutes, does not need to be peeled or processed in any way, nor does it need extensive cooking in large rock lined ovens. Fire cracked rock and ground stone tools are not indicators of its use.

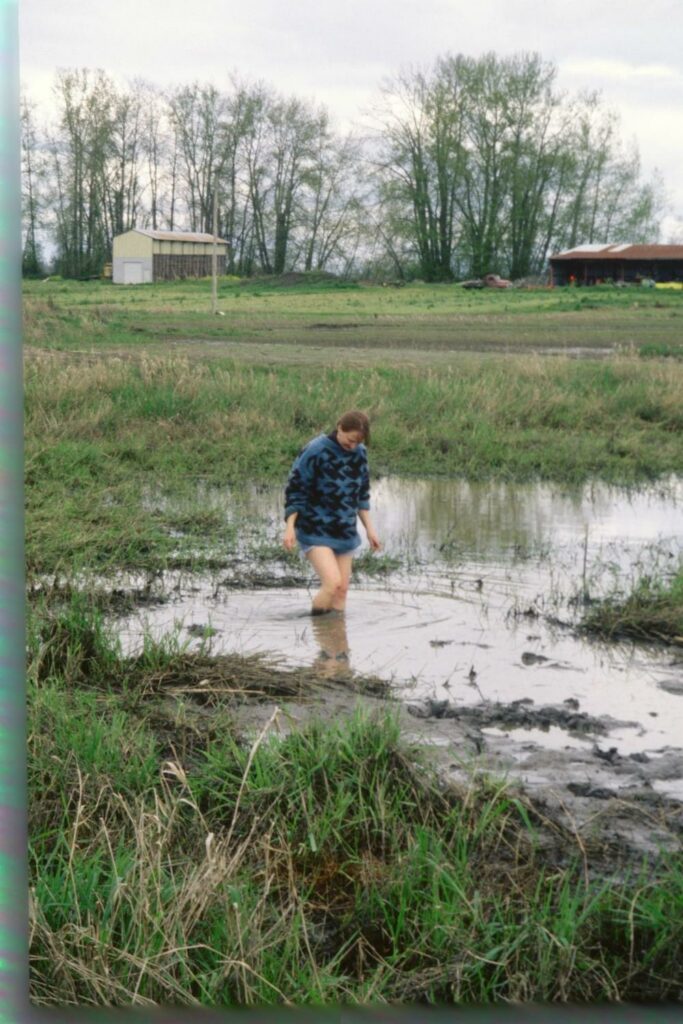

Large wapato wetlands like this one were once prolific on the lower Columbia. Before the carp were introduced into this environment in 1893, much of the lower Columbia shores, ponds sloughs and wetlands were extensive wapato wetlands.

These wapato wetlands were called by early writers ‘the great water gardens of the Indians’. These early accounts describe the ‘luxuriant growth’ of wapato patches. In a normal patch, there are approximately 28 plants to the square meter in a solid monoculture.

Wetlands (estuaries and marshes) are resilient because they are the most highly productive ecosystems in the world, producing between 8,800 and 9,600 kilocalories of energy per square meter per year. In comparison, temperate forests produce about 5,600 kilocalories per square meter annually, and agricultural land produces an average of only 2,400 kcal (Miller 1993:94). Wetland plant species such as Sagittaria latifolia are often r-strategists because they produce a large quantity of offspring, of which only a small percent survive to reproduce.

Sagittaria latifolia and waterfowl have co-evolved in a classically mutually beneficial relationship. Goose grubbing has been shown to increase the fitness of Sagittaria species. Geese and other waterfowl add nutrients, high in nitrogen to the wetland environment, contributing to the fitness of the wetland plants. They also contribute to the spreading of the plant by breaking up the rhizomes, allowing un-grazed rhizomes and tubers to raft to new locations and reestablish themselves. Waterfowl also assist in dispersing the seeds, which stick to the skin on their feet and legs, but are also eaten and subsequently redeposited, enabling the plant to colonize great distances very rapidly.

This ability to float assists the waterfowl when they graze, and makes it easier for human populations to gather the roots. In October while treading in the silty mud in a wapato patch in water at my knees, 113 tubers were released from the substrate and floated to the surface within a thirty-minute time period. There are 3.6 calories per dry gram of wapato and during this trial, I collected 1,505 grams (fresh) of wapato. Wapato can be harvested from the beginning of October to mid-May, a season of over 200 days during the coldest time of the year when game and other foraged resources are typically scarce. The most cost-effective times to recover wapato are October, and in spring from March to April, which corresponds to the biannual waterfowl migrations.

Sometimes the patches dry out, and the tubers can be dug up from dry ground as you see here.

There are several varieties of Sagittaria throughout the world, but they all have arrowhead shaped leaves, white or mostly white flowers and they produce tubers as the plants die back in the Fall. This last slide is a photograph of the Sagittaria latifolia page in Benjamin Smith Bartons book Elements of Botany, the first American textbook on botany which was published in 1803 and given to Lewis and Clark to take with them on their journey. Some of our best descriptions of the Native American use of wapato come from Lewis and Clark, on their journey to the Pacific Ocean in 1803-1806. Joseph Whitehouse, who also kept a journal recorded that they “ate some excellent roots which we found to eat nearly as good as potatos”. Patrick Gass wrote that same day : “The roots are of a superior quality to any I had before seen ; they are called whpto, resembel a potato when cooked and are about as big as a hens egg.” They noted that it grew in great profusion in this valley, and on November 5, 1805, Clark named the valley Wapato Valley, “Wap-pa-too Valley from that root or plants growing Spontaniously [sic] in this valley only”

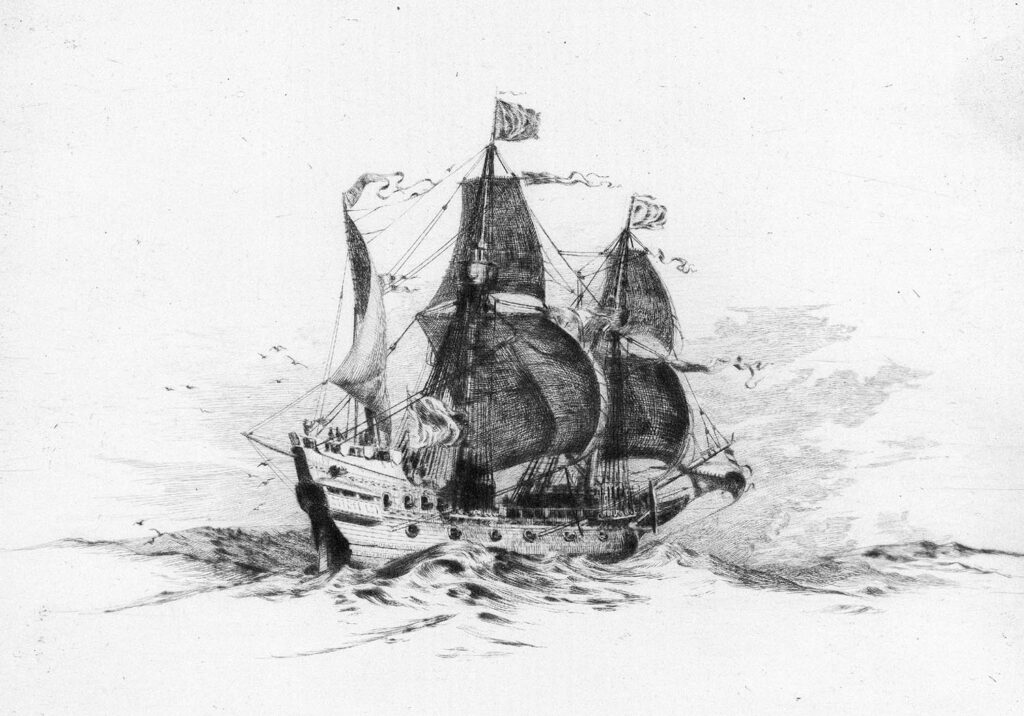

One early account of wapato may be from Francis Dake’s visit to the Oregon coast in 1579. When Drake and his crew in the Golden Hind made landfall the Native people gave them a root they called ‘Petah’ that could be eaten raw or made into cakes. The Native word Drake recorded for these cakes was ‘Cheep’. This is a remarkable sound and meaning correspondence for the Chinuk Wawa words for ‘wapato’ and ‘chaplil’, the root cake made with wapato. This suggests not only that Drake and his crew spent the summer of 1579 on the Oregon coast, but that a type of proto-Chinuk Wawa was already in place prior to any European encounters.

Today wapato is limited in the environment due to predation not only by carp but by cattle, as seen here. However, wapato is making a comeback as areas are protected, re-watered, or re-planted.

Unless otherwise noted, photographs by Melissa Darby